R-E-S-P-E-C-T: Find Out What It Means to Me

“Let us not speak of tolerance. This negative word implies grudging concessions by smug consciences. Rather, let us speak of mutual understanding and respect.” – Dominique Pire

I received a number of gracious comments and messages to my last blog entry thanking me for sharing my story of how hip-hop was an important platform to helping me to begin to understand the current opportunities and challenges facing the black community. I thought I would continue with the theme and talk a little more this week about how music more generally has helped me to reconcile a stance about engaging with other forms of diversity including sexuality and gender.

Since coming to Toronto in 1998, I have been enthralled with the many festivals held each summer that place a spotlight on the diversity in the city and various communities. Whether experiencing Greek cuisine at Taste of the Danforth or grooving to the rhythms of Caribana, there is something happening almost every week here between June and September. It truly is a hotbed for meeting individuals from all walks of life. The highlight though for many Torontonians is Pride. Culminating in late-June with one of the world’s largest parades, Pride is a month-long celebration of the local LGBTQIA community in Toronto (and perhaps Canada) and commemoration of the struggles faced by these communities around the world which first came to public consciousness during the Stonewall Riots in June 1969. There is dance, performance, dress, and positive expression of all kinds. For me though, it is also a subtle reminder of my fragility as a white male and acknowledgment that actions speak louder than words when it comes to how we treat those who identify differently than us.

Unlike my experiences with the black community and other ethnocultural groups since then, I was exposed more directly to sexual and gender diversity growing up. One of my uncles was openly gay. This fact created questions, which, in turn, motivated often illogical responses. In my case, it meant being kept away from him by my father as much as possible. My understanding in the years since my dad passed was that this stemmed from his unfounded belief that being gay was a virus which was contagious. As hard as that may be for some to understand, remind yourself of the hysteria around HIV and AIDS during the 1980s. Lack of knowledge of the disease bred misinformation which created assumptions and ultimately prejudice. I could probably count the amount of times on one hand that I spoke with my uncle at family gatherings over a 20-year span as a result. I was certainly never permitted to spend time with him as an adolescent without a parent being present. I was not even encouraged to really acknowledge his existence in the same way I did my other aunts and uncles. My uncle Ken, an actor, professor, and loving son/sibling, quietly passed a few years ago and it got me reflecting recently about how my experiences with him growing up may have impacted my stance for initially engaging with the LGBTQIA community more directly since then.

One instance which serves as a constant reminder to my fragility really stands out. Early on in my career while working for the University of Toronto, I was a clubs’ liaison for the Office of Student Affairs. One of the many groups I supported was Pride at UTSC. I started in this role around the time where the annual changeover in leadership was occurring and still hadn’t heard from the group’s new representatives. So, I thought I would reach out and introduce myself, and invite them to visit and meet. Harmless, right? I thus called the number for the person we had on-file. When someone answered and advised that the individual in question was not home, I left a brief message with my name and number and to have them call me back at the University at their earliest convenience. I did not say why I wanted to speak with them, but I realized very quickly afterward that I did not have too. Without even recognizing what I had done in the moment, I realized very quickly that this individual may not have yet come out to whoever that was I was speaking with. I was mortified. I am still mortified. While thankfully it did not result in unwanted questions for that individual, it did result in significant embarrassment for my colleagues and me. And worst yet, the situation broke trust with the student and community before trust could even be established.

Now, I do not consider myself to be prejudiced, but that is also easy to say when you’re a white male and everything has been made easier by virtue of my gender and skin color. The fact is that I cannot deny that I have been unconsciously biased at various points in my life. This is one such instance of that. In the days following the call, I really tried to understand what would have led me to assume that taking those steps was okay. After all, I grew up being exposed by my mother to the importance of empathy and feeling with individuals as opposed to just feeling for them. At the time, I thought it may have just been an honest oversight, but I have learned since that this was most definitely not the case. In fact, it was an instance in which I subconsciously prioritized tolerance above respect. And I believe that may have resulted in part from my early experiences—or lack thereof—with the LGBTQIA community, starting with my uncle Ken.

Tolerance has a hollow history in its vernacular of use relating to equity and inclusion. For those who grew up during the civil rights unrest of the 1960s, it was a term often used a catch-all to classify behaviours necessary for the improvement and advancement of oppressed minorities in white-dominated society. While often presented by both white and some oppressed minority leaders at the time as a solution to normalizing equality and unity between all people, what it really achieved was a relaxing of tensions amongst the white middle class by helping them to reconcile that differences can exist without having to really care to any extent. In other words, it legitimized the notion of “you stay in your lane and I’ll stay in mine,” while attempting to reduce the outward tensions that were prevalent then. And it hasn’t changed much since. More recently, for example, it has been used by some elected leaders in response to the recent BLM protests to justify why “all lives matter” as opposed to why black lives matter must exist as a prerequisite first. Make no mistake: just because tolerance was a word that was once embraced by some to advocate for equity and inclusion for a brief period (keeping in mind that it didn’t exist at all prior to then), it doesn’t mean that it’s appropriate or applicable in the current sense. In fact, it’s largely outdated and doesn’t account for the extreme discrimination that preceded its use then or now.

It was this latter tension though that piqued my interest about the intersection of music with other important social justice moments for both the black and LGBTQIA communities at the time. I was particularly curious about whether black music artists of the 1960s who identified as LGBTQIA may have advocated for tolerance to any extent and whether its use by them may have normalized such behaviour for whites. I was also interested about whether the outward use of the term changed at any point and to what extent this affected how white, heterosexual people might have viewed the subject then and now. So, I did some research. And, while it wasn’t easy to find many black artists who publicly identified as LGBTQIA during this time, I discovered one who provided a glimpse into what role tolerance might have played at the onset of civil unrest at this time.

An American singer who was a leading light of Toronto’s 1960s soul and R&B scene, Jackie Shane is now remembered for her dynamic stage presence, which drew comparisons to Little Richard and James Brown, and for her 1962 single “Any Other Way,” which was a modest chart hit across Canada. An early pioneer of Toronto’s transgender and LGBTQ community, Shane’s early days saw her performing on-stage as a man dressed in drag. Years later, she would come out publicly to identify as a transgender woman, but the unforgiving social atmosphere of the era made this somewhat ambiguous approach her safest bet. There are sparse recordings available of her work—a live album and a recent collection of studio tracks which have been combined with those live recordings in a terrific historical capsule that provides important insight on her impact. Her music is incredible. What really stood out though are the lyrics on the outro to her live recording of “Money” in which she raps (and I paraphrase) the following:

“Walking down the street, people point, laugh and whisper. That don’t worry [me]. I know I look good. My slogan is: do what you want if you know what you are doing. [Assuming] you don’t force your will or way on anybody else, live your life. No one is sanctified or holy. God bless the child that has their own, I have so much of my own. Now I know some of you know what I’m thinking about when I say there’s no point in talking together. I gotta have a little help. You don’t get to wear what I done made. You gotta help me and then we’ll live happy.”

These comments are revealing to me as they provide first-hand insight into what certain everyday individuals living as both black and LGBTQIA may have been feeling at the time. And those feelings weren’t necessarily aligned with the words that most white and even some community leaders were saying. Although tolerance was a logical first step towards equity and inclusion, it was only just a step that functioned in accordance with other seminal moments of the time as highlighted in the United States by Brown v. Board of Education, the Montgomery Sit-Ins, the March on Washington and even the Civil Rights Act itself. “Separate but equal” was only meant to be the start of progress. It wasn’t meant to be the extent of that progress. Unfortunately, with the assassinations of most black community leaders by the end of the 1960s and the eventual election of Richard Nixon who wholly embraced a re-imagining of the white, middle class, that outdated concept of tolerance continued to take hold. Eventually, with the shift to law and order and more punitive punishment of crime during the late 1970s and 1980s (particularly under Ronald Reagan), the concept of tolerance came to be seen as a reasonable provision championed by whites to address what they were saying they most often could expect from everyone else: lawlessness, anarchy, and disorder.

And, so, here we are now in 2020 faced with many of the same systemic problems that date back hundreds of years. To clarify, I am encouraged that protest has once again become a means for the voiceless to have a voice. I am also encouraged that it has resulted in some preliminary reform to laws and attitudes. But I am still skeptical (and I say that with the greatest amount of respect for those fighting right now on the frontlines of this battle). My experience in studying history is that the oppressor will always give in an inch to take a foot. We simply must expect more of each other this time. Harmony—and by extension, unity—may be a start, but justice and fairness in perpetuity for those most affected must be the goal. Otherwise, aren’t we all just continuing to perpetuate the same (in)tolerance that’s persisted for the last 50 years?

If you would like to get started in learning more about social injustice through music, consider some of these well-known recordings which have helped me to gain clarity of the importance of justice and fairness (respect) for all:

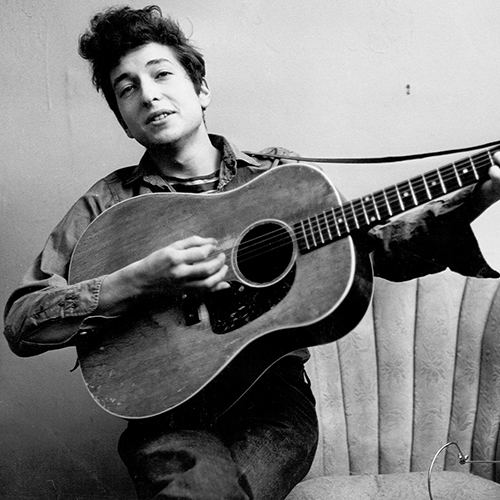

Bob Dylan, Blowin’ In the Wind:

Inarguably the peak of modern protest songwriting, “Blowin’ in the Wind” transformed Bob Dylan from hipster folky to cultural sensation and provided the growing protest community with an anthem equally applicable to every kind of injustice ever visited upon the Earth. As with most of his other classics, Dylan makes a complex song sound deceptively simple; in each of the three verses, he asks three rhetorical questions (i.e., “How many roads must a man walk down, before you call him a man?”), and answers each time with the chorus: “The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind/The answer is blowin’ in the wind.” While the questions speak to the unending record of injustice in the long history of the world, the answers reflect the Taoist mantra that the solution is obvious to all who truly think about it, yet impossible to grasp with any type of standard (i.e., written or expressed) explanation. Though it’s masked in naturalistic thinking, “Blowin’ in the Wind” is an encapsulation of Eastern thinking within abstract songwriting that (surprisingly) made the charts and (not so surprisingly) became one of the most famous standards of the rock era.

The Temptations, Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today):

Hands down, one of the Temptations’ most popular records, the Norman Whitfield/Barrett Strong song knocked you dead with socially conscious lyrics about the world’s and people’s woes, and had a driving beat that embedded in your brain and juiced your feet. The timing was right, too: right in the midst of the Vietnam conflict with an apropos title. It’s been redone by Duran Duran, Tina Turner, Love and Rockets, Opium Jukebox, and others.

The Isley Brothers, Fight the Power:

The song was sparked in a 1975 recording session in which guitarist Ernie Isley, inspired by the news, wrote two songs: “Fight the Power” and an anti-poverty ballad titled “Harvest for the World.” The song reflected a negative opinion of authority figures, a feeling shared by all the band members, which can explain the intensified vocalizing by Ron, Rudy, and Kelly. Later, the trio added in the background chant, “fight it!” to merge in with the brothers’ vocal ad-libbing near the end. “Time is truly wasting/There’s no guarantee/Smiles in the making/Fight the powers that be.” Nuff’ said.

The Creedence Clearwater Revival, Fortunate Son:

Lyrically, this song was one of songwriter John Fogerty’s strongest and most uncompromising statements. Too much, perhaps, has been made by some critics of a pro-working class and anti-privilege ethos in the song, with some seeing it as a blast against those wealthy families who were able to keep their sons out of Vietnam while less affluent people had fewer options. It’s more of a screed against the privileged in general, using and subscribing to patriotism while sending others to do the dirty work of fighting. At any rate, Fogerty — who, incidentally, did serve in the army reserve and knew something about having to pay the consequences of militarism — makes his stance on the matter clear, if blunt. That’s especially so in the chorus, where Fogerty hammers home the point again and again: it ain’t him, he’s not a fortunate son.

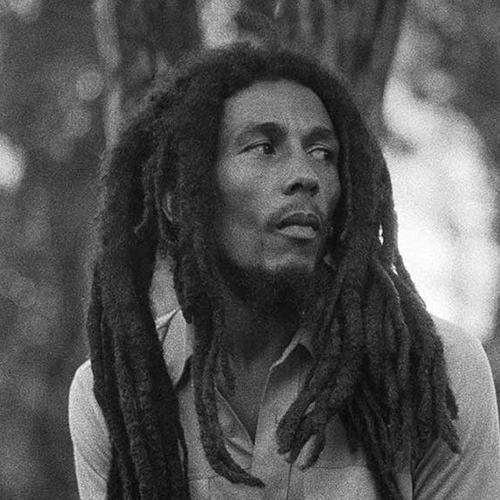

Bob Marley, Get Up, Stand Up:

The ultimate musical evocation of the Rastafarian aesthetic, and a worthy political or social protest song as well, “Get Up, Stand Up” blasts religious hypocrites and commands listeners to start thinking for themselves. The song, composed by Marley with Peter Tosh and recorded for his excellent Burnin‘ LP from 1973, includes three verses dealing with what is, according to Rastas, common misconceptions about the world often accepted by religious persons. The punchy singalong chorus then proclaims, “Get up, stand up, stand up for your right/Get up, stand up, don’t give up the fight.” It’s also been recorded by reggae artists Toots & the Maytals, Shabba Ranks, and Spear of Destiny, and is also used as an anthem by Amnesty International.

Bob Marley, Redemption Song:

One of the few songs in Bob Marley’s discography without the characteristic reggae rhythm, the acoustic protest song “Redemption Song” closed the final album released during his lifetime. Echoing several of Marley’s favorite themes (empowerment, psychological as well as physical freedom), “Redemption Song” includes surreal yet powerful images reminiscent of Bob Dylan’s mid-’60s work. Marley calls up the history of slavery in the first verse with talk of pirates and merchant ships, then applies it to the present day by reminding listeners that “mental slavery” still takes place. Finally, Marley leaves us with the thought, “Won’t you help to sing, these songs of freedom/cause all I ever had, redemption songs.”

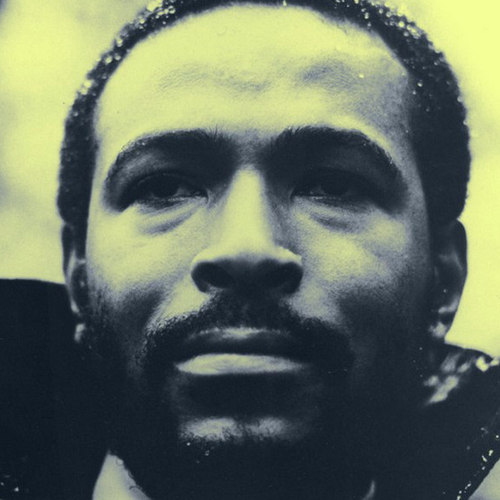

Marvin Gaye, Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler):

It wouldn’t tell the following year that Curtis Mayfield’s classic Superfly soundtrack would be released, yet Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues (Makes Me Wanna Holler)” has some of the rich imagery that would make that album so poignant and influence hip-hop/rap artists decades later. It’s a credit to Gaye’s amazing talent that he could still, after years of having international hits, relate to the travails of inner-city life. Though he sang in a smooth tenor, Gaye’s pain and anger shines through. A single from his gold masterpiece What’s Going On, “Inner City Blues (Makes Me Wanna Holler)” went to number one R&B for two weeks and number nine pop in late 1971.

Gil Scott-Heron, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised:

A poem and song, Scott-Heron first recorded it for his 1970 album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, on which he recited the lyrics, accompanied by congas and bongo drums. A re-recorded version, with a full band, was the B-side to Scott-Heron’s first single, “Home Is Where the Hatred Is“, from his album Pieces of a Man (1971). The song’s title was originally a popular slogan among the 1960s Black Power movements in the United States. Its lyrics either mention or allude to several television series, advertising slogans, and icons of entertainment and news coverage that serve as examples of what “the revolution will not” be or do. The song is a response to the spoken-word piece “When the Revolution Comes” by The Last Poets, from their eponymous debut, which opens with the line “When the revolution comes some of us will probably catch it on TV.”

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Ohio:

A protest song and counterculture anthem written and composed by Neil Young in reaction to the Kent State shootings of May 4, 1970, “Ohio” was performed by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. An article in The Guardian in 2010 describes the song as the ‘greatest protest record’ and ‘the pinnacle of a very 1960s genre,’ while also saying ‘The revolution never came.’ The lyrics help evoke the turbulent mood of horror, outrage, and shock in the wake of the shootings, especially the line “four dead in Ohio,” repeated throughout the song. “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming” refers to the Kent State shootings where Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four students. Crosby once stated that Young keeping Nixon’s name in the lyrics was “the bravest thing I ever heard.” The American counterculture took the group as its own after this song, giving the four a status as leaders and spokesmen they would enjoy to a varying extent for the rest of the decade.

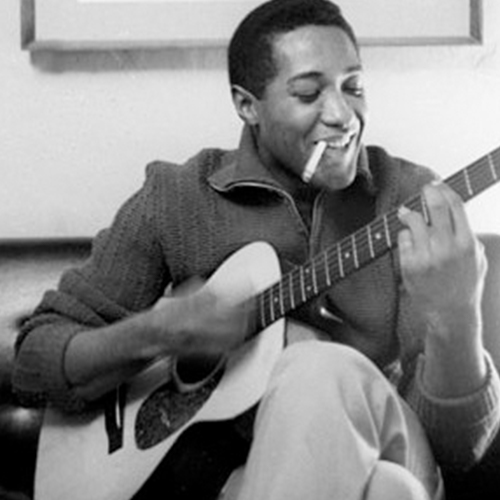

Sam Cooke, A Change is Gonna Come:

Recorded as a response to “Blowin’ In the Wind” by Bob Dylan, the song melded gospel, blues, and protest elements into an emotional statement by a black man about where he had come from and where he and his people were going. The song was inspired by various personal events in Cooke’s life, most prominently an event in which he and his entourage were turned away from a whites-only motel in Louisiana. Cooke felt compelled to write a song that spoke to his struggle and of those around him, and that pertained to the Civil Rights Movement and African Americans. The song contains the refrain, “It’s been a long time coming, but I know a change is gonna come.” Making the Top 40 of the pop charts and the Top Ten of the R&B chart instantly, and it began to spread as an anthem of the civil rights movement, earning covers from prominent R&B performers like Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin.

Day One Listens is written by Allan Grant, Chief Operating Officer of Day One Leadership. Through stories of how music has influenced key parts of his life, he will regularly profile artists and albums that have created lasting impact; helped him to grow over time; and practice self-respect every day. The author graciously acknowledges the contributions of various online reviewers who aided in providing insights and remarks related to the specific albums mentioned.