Day One Listens – A Brief Introduction to my Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm

“I guess hip-hop has been closer to the pulse of the streets than any music we’ve had in a long time. It’s sociology as well as music, which is in keeping with the tradition of black music in America.”

― Quincy Jones

I acknowledge my privilege. As a white, heterosexual male, I’ve been given every benefit and opportunity possible. I’ve never been called a racial slur; pulled over by law enforcement because of my skin colour; denied service; or subjected to maltreatment of any kind. I don’t look over my shoulder when walking down the street. I’ve gotten most things I’ve ever wanted. I’m free in pretty much every sense. And, yet, it doesn’t feel good. Perhaps, never has. My freedom, regardless of the good I’ve attempted to use it for, has always come at a significant cost. For every benefit I’ve ever received, someone of color hasn’t garnered the same opportunity. They’ve struggled mightily to convince perfect strangers of their worth because of false notions that certain skin colours mean strength. They’ve been unfairly targeted for historical perceptions rooted in hate. They’ve been marginalized without any attempt to empathize. They’ve died. This is not simply unfortunate and easily corrected as some well-known individuals in power have implied. It’s inherently unfair and despicable. It’s systemic.

I didn’t have to learn these lessons by treating someone as they didn’t wish to be treated. Despite being raised in a typical nuclear household, I frequently witnessed attempts to rewrite the plight of the marginalized and underprivileged through the lens of an angry male who often could only provide respect when it was painted white. I don’t fault my father per se. We’re all influenced by our unique experiences. He grew up during the War in a large household vying for the attention of an absentee father, so, to some extent, it’s easy to understand why he would prioritize his needs above all else as he got older. It’s especially easy to understand why he often put trust in what he knew. And he didn’t personally know any black people. Only those portrayed in film or on the news as criminals, hoodlums, or malcontents (as if those characterizations were exclusive to only the black community). My mother is different. She feels strongly with the marginalized and underprivileged. I suspect it’s in part because she’s a product of her time. She was a “flower child.” Social justice was part of getting a degree in the school of hard knocks during the 1960s. Since then, she’s used those experiences and insights gained to build a life centered upon helping people. Prior to retiring a month ago, she’d been a Personal Support Worker for elderly people from all races, creeds, and beliefs. Simple tolerance doesn’t exist in her language. Only respect without qualification.

My mother and father set the stage for my exploration on race and equity. However, as an adolescent growing up in small-town Ontario, it wasn’t easy learning about diverse communities of people who were different than me. So, I improvised as best a teenager could: I used music. Every weekday from Grade 7 through the end of high school, I religiously watched Rap City on BET. On Saturdays, I watched Soul Train on WGN. I was often shunned and laughed at by my white classmates because of this. But I listened and learned, regardless. This might seem atypical of a white person for those individuals who live with injustice every day. Again, I acknowledge my privilege. But these experiences meant something to me—and still do. Hip-hop music was my gateway to beginning to understand both why and how black lives matter, a journey which continues to evolve as I traverse new discoveries in soul, funk, blues and jazz music.

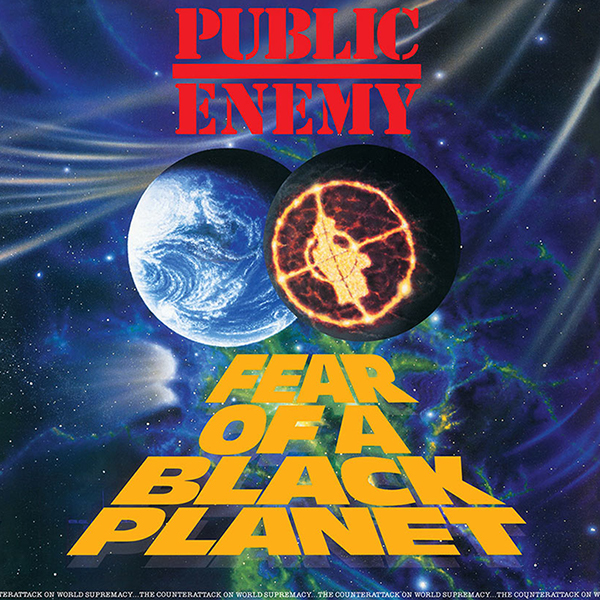

The first rap album I ever purchased (or rather my mother purchased for me) was Public Enemy’s “Fear of a Black Planet.” Released in March 1990, this record was made “during the golden age of sampling, before legal limits were set on sampling, so this is a wild, endlessly layered record filled with familiar sounds you can’t place. Chuck D’s writing was tight, with each track tackling a specific topic (apart from the “Welcome to the Terrordome,” whose careening rhymes and paranoid confusion are all the more apparent when surrounded by such detailed arguments), a sentiment that spills over to Flavor Flav, who delivers the pungent humor of “911 Is a Joke,” perhaps the best-known song here. Chuck gets himself into trouble here and there — most notoriously on “Meet the G That Killed Me,” where he skirts with homophobia — but by and large, he’s never been so eloquent, angry, or persuasive as he is here.” The gold standard though is the final track on the album, “Fight the Power.” Consider the following lyrics through the lens of recent events:

As the rhythm designed to bounce

What counts is that the rhymes

Designed to fill your mind

Now that you’ve realized the pride’s arrived

We got to pump the stuff to make us tough, From the heart

It’s a start, a work of art

To revolutionize make a change nothing’s strange

People, people we are the same

No we’re not the same

‘Cause we don’t know the game

What we need is awareness, we can’t get careless

You say what is this?

My beloved let’s get down to business

Mental self defensive fitness

(Yo) bum rush the show

You gotta go for what you know

To make everybody see, in order to fight the powers that be.

Powerful stuff. Rarely has there been a combination of conscious lyrics and head-popping groove (thanks largely to James Brown and his classic cut, “The Funky Drummer”) as potent in hip-hop for me as this track. In just under 5 minutes (or 7+ if you watch the extended video cut), it plainly revealed the stirring emotions and feelings of a community that have been unfairly and historically labelled as other. It is angry and poignant. It is specific about portraying the goalposts of what is reasonable and fair for engaging with individuals and cultures who don’t enjoy the same luxuries as my own. It is also just as relevant today, despite providing the impetus to keep listening and learning then.

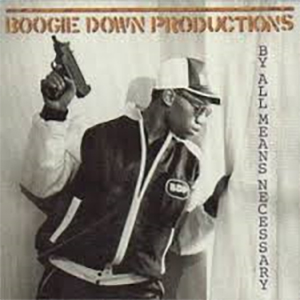

For the last 27 years, I’ve been a keen student. I’ve gone to numerous shows. My first was in ’96 featuring The Roots with Parliament Funkadelic as the opener if you can believe it. My favourites were Gang Starr at Maple Leaf Gardens just prior to their break-up and Dilated Peoples with Talib Kweli and The Arsonists at The Opera House. I’ve bought thousands of albums, sometimes two and three times over (a summary of some of the absolute best can be found below). I’ve also engaged with some of hip-hop’s most revered pioneers through my path of discovery in the genre. My favourite story was acquiring and subsequently trading a test pressing vinyl of “Poetry b/w Elementary” by Boogie Down Productions with Kenny Dope of the Masters at Work production crew. I’ll never forget getting a random email from him after winning the auction for the single proclaiming that “he needed the record; couldn’t find it elsewhere and was willing to give up what I wanted to get it.” After a brief negotiation, I came away with a collection of 10 of the rarest records out at the time including the 93’ till Infinity blue vinyl, Diamond D’s first record, Special Ed’s “I Got It Made” single with that fantastic Ripple sample, and a Breakin’ Atoms first pressing. And, ultimately, hip-hop was one of the primary reasons why I decided to transfer out of physics and math during my undergraduate years to focus my studies on the American experience with an emphasis on race relations.

To put it simply, my journey with hip-hop has provided as valuable an education as any diploma or degree that I’ve obtained. It’s given me a glimpse of the human condition at both its best (raising awareness and advocating for meaningful change for communities in crises) and worst (glorifying violence, misogyny, and homophobia). More importantly, it’s exposed me to the value of human connection with those who don’t look like or value the same things as I to help open my eyes to the possibilities of being able to create meaningful impact for myself and others. And it’s reinforced to me that if leadership is possible in this era of significant social crisis, it’ll be because we, who identify as privileged, stop oppressing the basic freedoms of the black community (and other racialized minorities) through ignorance and inaction and instead employ all means necessary to work alongside them to institute meaningful social progress and reform. Fight the power, indeed.

If you would like to start a journey of your own, consider these albums which have fostered increased social awareness for me:

Boogie Down Productions, By All Means Necessary: The murder of DJ Scott La Rock had a profound effect on KRS-One, resulting in a drastic rethinking of his on-record persona. He emerged afterwards with this album, calling himself “The Teacher” and rapping mostly about issues facing the black community. His reality rhymes were no longer morally ambiguous, and this time when he posed on the cover with a gun, he was mimicking a photo of Malcolm X. Lyrics from this album have been sampled by everyone from Prince Paul to N.W.A, and it ranks not only as KRS-One’s most cohesive, fully realized statement, but a landmark of political rap that’s unfairly lost in the shadow of the next album featured below.

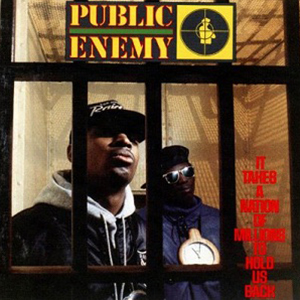

Public Enemy, It Takes a Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back: On this album, Chuck D marshaled considerable revolutionary force, clear vision, and a boundless vocabulary to create galvanizing, logical social arguments that were undeniable in their strength. They only gained strength from Flavor Flav’s frenzied jokes, which provided a needed contrast. What’s amazing is how the words and music become intertwined, gaining strength from each other. Though this music is certainly a representation of its time, it hasn’t dated at all. It set a standard that few could touch then, and even fewer have attempted to meet since.

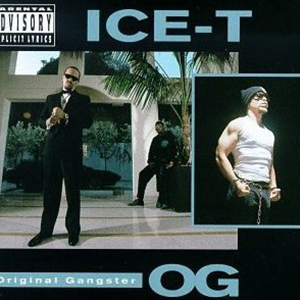

Ice-T, Original Gangster: One of gangsta rap’s defining albums, Original Gangster is a sprawling masterpiece that stands far and away as Ice-T’s finest hour. There’s perceptive social analysis, chilling violence, psychological storytelling, hair-trigger rage, pleas for solutions to ghetto misery, cautionary morality tales, and cheerfully crude humor in the depictions of sex and defenses of street language. But with a few listens, it’s possible to assimilate everything into a complex, detailed portrait of Ice-T’s South Central L.A. roots — the album’s contradictions reflect the complexities of real life. That’s why the more intelligent, nuanced material isn’t negated by the violence and sexism — both of which, incidentally, are held relatively in check, with the former having been reshaped into a terrifying but inescapable fact of life.

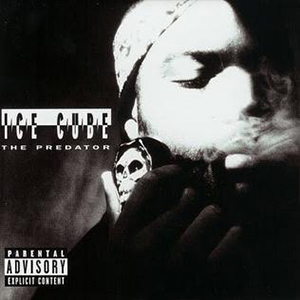

Ice Cube, The Predator: Released in the aftermath of the 1991 L.A. riots, The Predator radiates tension. Ice Cube infuses nearly every song, and certainly every interlude, with the hostile mood of the era. Given this, it’s not one of Ice Cube’s more accessible albums despite boasting a few of his biggest hits. It is his most serious album, though, as well as his last important album of the 90s.

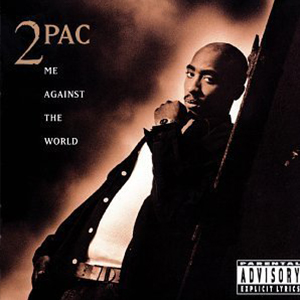

2Pac, Me Against the World: Recorded following his near-fatal shooting in New York, and released while he was in prison, Me Against the World is the point where 2Pac really became a legendary figure. Having stared death in the face and survived, he was a changed man on record, displaying a new confessional bent and a consistent emotional depth. By and large, this isn’t the sort of material that made him a gangsta icon; this is 2Pac the soul-baring artist, the foundation of the immense respect he commanded in the hip-hop community.

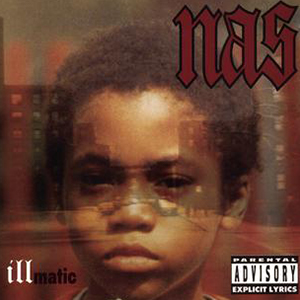

Nas, Illmatic: This album helped spearhead the artistic renaissance of New York hip-hop in the post-Chronic era, leading a return to street aesthetics. Yet even if Illmatic marks the beginning of a shift away from Native Tongues-inspired alternative rap, it’s strongly rooted in that sensibility. For one, Nas employs some of the most sophisticated jazz-rap producers around: Q-Tip, Pete Rock, DJ Premier, and Large Professor, who underpin their intricate loops with appropriately tough beats. But more importantly, Nas takes his place as one of hip-hop’s greatest street poets — his rhymes are highly literate, his raps superbly fluid regardless of the size of his vocabulary. He’s able to evoke the bleak reality of ghetto life without losing hope or forgetting the good times, which become all the more precious when any day could be your last. As a narrator, he doesn’t get too caught up in the darker side of life — he’s simply describing what he sees in the world around him.

Day One Listens is written by Allan Grant, Chief Operating Officer of Day One Leadership. Through stories of how music has influenced key parts of his life, he will regularly profile artists and albums that have created lasting impact; helped him to grow over time; and practice self-respect every day. The author graciously acknowledges the contributions of various online reviewers who aided in providing insights and remarks related to the specific albums mentioned.